Jeden jedyny kamień zadecydował o losach wspinaczki. W którym miejscu byłby współczesny alpinizm, gdyby Alex Macintyre nie zginął na południowej ścianie Annapurny? Nie wiemy, lecz dzięki fascynującej książce Johna Portera możemy przenieść się w piękny, wspaniały świat brytyjskiego i polskiego alpinizmu przełomu lat 70. i 80. Przedstawiciele obu nacji z równą swadą, jak się okazuje, stawali czoła drogom wspinaczkowym o wysokiej wycenie, jak i licznym butelkom trunku o … wysokiej wycenie. „Niezależnie od tego czy wspinając się na zasiłku w Wielkiej Brytanii czasów Margaret Thatcher, czy na kominach komunistycznej Polski, obie grupy wspinaczy uczyły się stawiana czoła trudnościom i przeciwnościom – na własnych warunkach”. [Scroll down for English version]

Jeden jedyny kamień zadecydował o losach wspinaczki. W którym miejscu byłby współczesny alpinizm, gdyby Alex Macintyre nie zginął na południowej ścianie Annapurny? Nie wiemy, lecz dzięki fascynującej książce Johna Portera możemy przenieść się w piękny, wspaniały świat brytyjskiego i polskiego alpinizmu przełomu lat 70. i 80. Przedstawiciele obu nacji z równą swadą, jak się okazuje, stawali czoła drogom wspinaczkowym o wysokiej wycenie, jak i licznym butelkom trunku o … wysokiej wycenie. „Niezależnie od tego czy wspinając się na zasiłku w Wielkiej Brytanii czasów Margaret Thatcher, czy na kominach komunistycznej Polski, obie grupy wspinaczy uczyły się stawiana czoła trudnościom i przeciwnościom – na własnych warunkach”. [Scroll down for English version]

„One day as a tiger” to świadectwo czasów, których już nie ma, ale które ukształtowały współczesną wspinaczkę, to epitafium wizjonerskiego pokolenia brytyjskich oraz polskich wspinaczy. To książka, której fragmenty powinien współtworzyć Voytek Kurtyka…

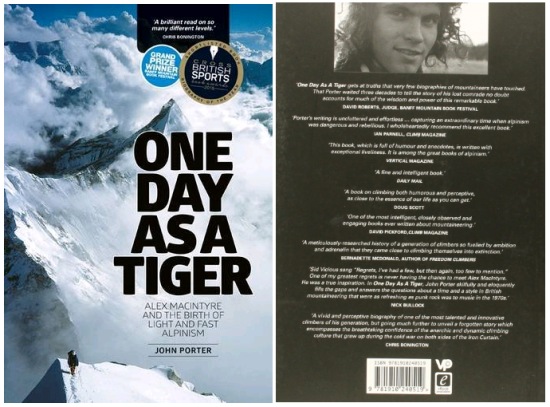

Po tym jak w 2014 roku na festiwalu w Banff zatriumfowała książka Johna Portera „One day as a tiger” z niecierpliwością oczekiwałem na paczkę z egzemplarzem zakupionym w brytyjskiej księgarni internetowej. Książka zapowiadała się bardzo ciekawie. Partner wspinaczkowy Alexa Macintyre’a po blisko 35 latach napisał książkę o tym legendarnym brytyjskim wspinaczu, z którym, wraz z Wojtkiem Kurtyką, tworzyli zręby stylu alpejskiego w górach wysokich.

Po tym jak w 2014 roku na festiwalu w Banff zatriumfowała książka Johna Portera „One day as a tiger” z niecierpliwością oczekiwałem na paczkę z egzemplarzem zakupionym w brytyjskiej księgarni internetowej. Książka zapowiadała się bardzo ciekawie. Partner wspinaczkowy Alexa Macintyre’a po blisko 35 latach napisał książkę o tym legendarnym brytyjskim wspinaczu, z którym, wraz z Wojtkiem Kurtyką, tworzyli zręby stylu alpejskiego w górach wysokich.

Alex Macintyre (1954 – 1982) to czołowa postać brytyjskiego alpinizmu swoich czasów. Mimo iż w momencie śmierci miał jedynie 28 lat, był prekursorem lekkiej i relatywnie szybkiej wspinaczki w małych zespołach w najwyższych górach świata. W stylu alpejskim wytyczał nowe drogi na himalajskich gigantach takich jak Dhaulagiri, Changabang lub Koh-i-Bandaka w Hindukuszu, a wiele ze swoich najważniejszych dróg pokonał wraz z Polakami, m.in. Jerzym Kukuczką i Wojtkiem Kurtyką. Z tym ostatnim dzielił wspólną wizję czystej formy alpinizmu w górach wysokich. Obok wspinaczki opracowywał nowatorskie rozwiązania, lżejszego, bardziej funkcjonalnego sprzętu, torując drogę dla nowoczesnej branży outdoorowej. Był przy okazji człowiekiem niezwykle inteligentnym, wesołym, przyjacielskim, acz nie pozbawionym wad.

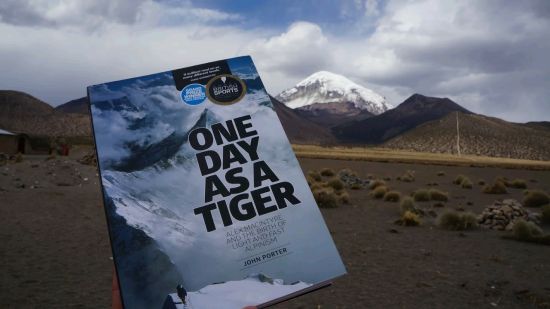

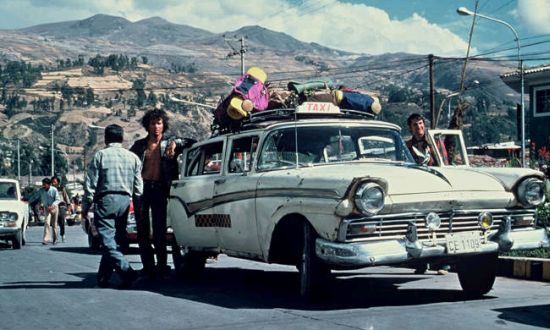

Głównego bohatera książki polubiłem od razu….i chwilę potem, po przeczytaniu raptem sześciu stron, serce podeszło mi do gardła, gdy trafiłem na opis śmiertelnego wypadku Alexa na Annapurnie w 1982 roku. John Porter jest bezlitosny i nie owija w bawełnę: ta książka jest o budzącym wielkie nadzieje pokoleniu wspinaczy, które „zawspinało” się na śmierć. Po mocnym wstępie autor cofa się do początków kariery wspinaczkowej i powoli przeprowadza nas przez życie Alexa – przez wydarzenia, które ukształtowały jego naturę i styl – jednocześnie z delikatnością pozwala nam zaglądnąć do prywatnego życia Maxintyre’a, posłuchać opowieści jego matki, przyjaciół, jego życiowych partnerek. Opowieść ta przetykana jest wspomnieniami z wypraw w góry: początkowo ze skalnej szkoły Lake District i gór Szkocji, następnie Alp, aż po najważniejsze wyprawy w Hidukusz, Himalaje, Andy Peruwiańskie. Co ciekawe dla polskiego czytelnika, autor zagląda także za Żelazną Kurtynę, do Polski końca lat 70. i początku 80., opisując wspomnienia z wizyt w naszym kraju, które odbył z ramienia British Mountaineering Council (odpowiednika naszego PZA) oraz wspólnych wypraw z czołowymi polskimi wspinaczami – z Andrzejem Zawadą, Wojtkiem Kurtyką, Janem Wolfem i innymi.

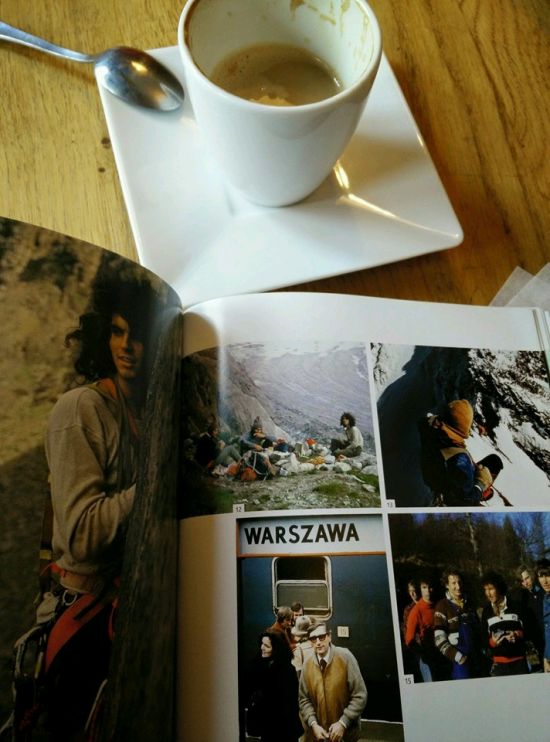

John Porter przeplata swoją opowieść licznymi anegdotami z życia wspinaczy. Szczególnie barwne opowieści pochodzą właśnie z odwiedzin w komunistycznej Polsce. Fascynujące jest spojrzenie Brytyjczyków na Polskę końca lat 70., próby zrozumienia zupełnie niepojętego procederu przemytu wszystkiego co się da sprzedać, a wręcz zarabiania na wyprawach w góry wysokie. Jak się okazuje, z przemycanych towarów korzystały też służby bezpieczeństwa komunistycznego ustroju. Odwiedzamy wraz z autorem Tatry zimą, gdzie w trakcie wspinaczki granią, po biwaku, Brytyjczycy natykają się na czechosłowacką straż graniczną. Obserwujemy fascynującą partię pokera, w której po jednej stronie zasiadają wspinacze, po drugiej partyjni aparatczycy. Frapujące są opowieści o tym, jak Andrzej Zawada przemycał Brytyjczyków pociągiem przez terytorium ZSRR w środku zimnej wojny. Gdy ci, nie do końca świadomi zagrożenia grali w przedziale w karty i słuchali Led Zeppelin, z głośników w pociągu uroczyście śpiewał Chór Armii Czerwonej i nijak nie dało się wyłączyć tej muzyki. Zawada pożyczył czekan Macintyre’a i metodycznie zaczął rozbijać głośniki w całym wagonie, aż Chór zamilkł. Oddając czekan oszołomionym Brytyjczykom oznajmił: „W Polsce nie pozwalamy na taki militaryzm i brak dobrego smaku”. Stosunek Zawady do sowieckiej Rosji odzwierciedla również komentarz do wręczenia w Moskwie szkockiej whisky jako łapówki: „Polska wódka jest o wiele za dobra dla tych Ruskich. Dawać im szkocką to zbrodnia”. Podobnych opowieści w książce jest mnóstwo, zarówno o Polakach – np. o konflikcie Wojtka Kurtyki z mieszkańcami afgańskiej wioski o kamień szlachetny, jak i o wspinaczach ze Zjednoczonego Królestwa.

John Porter przeplata swoją opowieść licznymi anegdotami z życia wspinaczy. Szczególnie barwne opowieści pochodzą właśnie z odwiedzin w komunistycznej Polsce. Fascynujące jest spojrzenie Brytyjczyków na Polskę końca lat 70., próby zrozumienia zupełnie niepojętego procederu przemytu wszystkiego co się da sprzedać, a wręcz zarabiania na wyprawach w góry wysokie. Jak się okazuje, z przemycanych towarów korzystały też służby bezpieczeństwa komunistycznego ustroju. Odwiedzamy wraz z autorem Tatry zimą, gdzie w trakcie wspinaczki granią, po biwaku, Brytyjczycy natykają się na czechosłowacką straż graniczną. Obserwujemy fascynującą partię pokera, w której po jednej stronie zasiadają wspinacze, po drugiej partyjni aparatczycy. Frapujące są opowieści o tym, jak Andrzej Zawada przemycał Brytyjczyków pociągiem przez terytorium ZSRR w środku zimnej wojny. Gdy ci, nie do końca świadomi zagrożenia grali w przedziale w karty i słuchali Led Zeppelin, z głośników w pociągu uroczyście śpiewał Chór Armii Czerwonej i nijak nie dało się wyłączyć tej muzyki. Zawada pożyczył czekan Macintyre’a i metodycznie zaczął rozbijać głośniki w całym wagonie, aż Chór zamilkł. Oddając czekan oszołomionym Brytyjczykom oznajmił: „W Polsce nie pozwalamy na taki militaryzm i brak dobrego smaku”. Stosunek Zawady do sowieckiej Rosji odzwierciedla również komentarz do wręczenia w Moskwie szkockiej whisky jako łapówki: „Polska wódka jest o wiele za dobra dla tych Ruskich. Dawać im szkocką to zbrodnia”. Podobnych opowieści w książce jest mnóstwo, zarówno o Polakach – np. o konflikcie Wojtka Kurtyki z mieszkańcami afgańskiej wioski o kamień szlachetny, jak i o wspinaczach ze Zjednoczonego Królestwa.

„One day as a tiger” jest dla brytyjskiego alpinizmu tym, czym dla polskiego była książka Bernadette McDonald „Freedom climbers”. Poznajemy legendarne postacie Anglików, którzy bardzo wiele osiągnęli w górach, wytyczając nowe drogi i nowe standardy, a nie są często dobrze znani polskiemu czytelnikowi. W książce historie o wspinaczce przeplatane są opowieściami o życiu codziennym alpinistów na Wyspach, o tym jak radzili sobie w pracy, w relacjach, w rodzinach. Te bardzo ciekawe wątki pozwalają na lepsze wejście w życie bohaterów, odzierają ich ze statusu nadludzi, którzy zdobywają najtrudniejsze góry, prezentują trudności w funkcjonowaniu na nizinach, ich pogubienie, cenę, jaką przyszło im zapłacić za styl życia, który wybrali. Rozmowy z najbliższymi Alexa są świadectwem tragizmu sytuacji, zdaje się bez wyjścia. Pasja, która sprawia, że Alex był kim był, która dała mu dojrzałość, jest pasją niezmiernie egocentryczną. Trudno znaleźć w niej miejsce na szczęście innych osób. Ta pasja wymaga jednak wsparcia innych, a oddający się jej człowiek domaga się bycia kochanym, pragnie wspólnoty z innymi i w miarę stabilnego życia po powrocie z gór. Książka prezentuję drogę Macintyre’a ku doskonałości stylu wspinaczki, dla której poświęcał on coraz więcej ze swojej natury, z relacji z przyjaciółmi. Każdy krok ku kolejnym, coraz trudniejszym wyzwaniom wymagał od niego coraz mniejszej wrażliwości na problemy innych, a coraz większego skupienia na konkretnym celu.

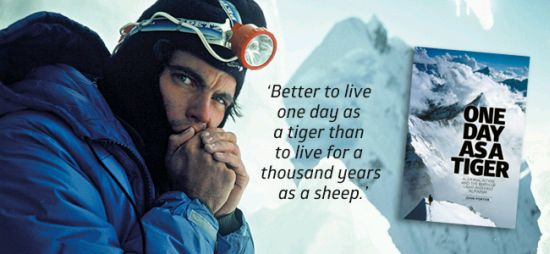

Alex MacIntyre (po lewej) i John Porter/Mount Everest Foundation

Podczas lektury wielokrotnie zostajemy zaproszeni do filozoficznych wręcz rozważań nad sensem wspinaczki, nad jej pięknem, nad tym co daje i co odbiera. John Porter zdaje się stawiać pytanie: jak kroczyć drogą pasji, by się nie zagubić, by nie zrobić jednego kroku za daleko, by nie podbić ceny wyżej, niż jest się gotowym zapłacić. Często odpowiedzi na te pytania przychodzą w postaci zgorzknienia i wyrzutów o wiele lat za późno. Idealnym stanem równowagi opisywanym przez autora jest moment, gdy poczuł on, przed wejściem w bardzo niebezpieczną ścianę Koh-i-Bandaka, że nie ma w przeszłości niczego, czego chciałby się trzymać, nie ma w przyszłości niczego, o co chciałby się starać, że nie ma nic poza tu i teraz.

Czytanie „One day as a tiger” to wielka przyjemność również za sprawą żywego języka autora. John Porter opisuje kolejne wydarzenia i przygody w tak barwny sposób, że nie sposób się oderwać od lektury. Język książki jest bardzo plastyczny, kreatywny i często sięga do slangu wspinaczy przełomu lat 70/80. Przetłumaczenie książki z równym polotem na język polski będzie wielkim wyzwaniem dla tłumacza. Jednym z niesamowitych smaczków przygotowanych przez autora jest nadanie poszczególnym rozdziałom tytułów nawiązujących wprost do piosenek i kultury tamtych dni. „Stairway to heaven”, „A walk on the wild side”, „Rocking in the free world” opisujące wspinaczkę za Żelazną Kurtyną, „Let it be”, w którym autor spotyka się z osieroconą matką, „Wish you were here”…

Książka jest ze wszech miar godna polecenia i, w mojej opinii, wejdzie do kanonu literatury górskiej. To fantastycznie napisana i opowiedziana historia czasów, które już dawno minęły, ale wbrew pozorom mają wiele wspólnego naszą rzeczywistością. Dla tych, którzy mogą sobie na to pozwolić polecam lekturę oryginału w oczekiwaniu na polskie wydanie. Czytając „One day as a tiger” rozmyślałem, ile wygody ja byłbym w stanie poświęcić dla przeżycia tego, co Alex, jak daleko byłbym w stanie ryzykować życie, jak długo tkwić w wyczerpaniu, w ciągłym napięciu? Dla Alexa Macintyre’a, jak się wydaje, nie było innej drogi, wolał „przeżyć jeden dzień jak tygrys, niż tysiąc lat jak owca”.

Tekst i tłumaczenie: Mateusz Gątkowski

One single stone had changed the fate of the climbing. Where would the modern alpinism be, had Alex Macintyre not died on the south face of Annapurna? We do not know, but thanks to a fascinating book written by John Porter we can immerse ourselves into a brave, beautiful world of the British and Polish alpinism at the turn of the 70s. (As it occurs, representatives of both nations with equal boldness faced highly valuated climbing routes and many bottles of … highly valuated liquid). “Whether climbing on the dole in Britain or forced to make a dangerous living as a roped access worker in Poland, both groups developed the skills needed to face hardship and adversity – but on climbers’ own terms”

“One day as a tiger” is an account of the times already gone, but which have shaped modern alpinism. It is an epitaph of visionary generation of the British and Polish climbers. It is a book, which should have been co-authored by Voytek Kurtyka.

After the 2014 Banff festival was conquered by John Porter’s book “One day as a tiger”, I waited impatiently for the delivery of the parcel, I’ve ordered at the British internet bookshop. The book was very promising: after nearly 35 years climbing partner of Alex Macintyre wrote a book about the legendary climber, with whom and Voytek Kurtyka, they created foundations of the alpine style in the high mountains.

Alex Macintyre was a leading figure of the British alpinism of his times. Even though he was only 28 when he died tragically, he was a precursor of light and fast climbing in small teams in the highest mountains of the world. He traced new routes, climbing in the alpine style on the Himalayan giants like Dhaulagiri, Changabang or in Hindukush Koh-i-Bandaka. He completed many of the most important routes with Poles, among others with: Jerzy Kukuczka and Voytek Kurtyka. With the latter he shared the common vision of a new, pure form of alpinism in high mountains. Apart from climbing he used to design lighter and more functional gear, paving the way for a modern outdoor industry. In addition to all the above he was a very intelligent, joyful and friendly man, not without flaws though.

I got to like the protagonist of the book at a spot … and the next moment, just after having read six pages of the book, my heart stopped beating when I stumbled upon a description of Alex’s lethal accident on Annapurna in 1982. John Porter is ruthless and does not beat around the bush: this book is about a very perspective generation of climbers, that climbed itself to death. After the bold start author returns to the beginnings and walks us through Alex’s life, through the events that created his nature and style. At the same time with a great deal of gentleness allows us to take a peek into Macintyre’s private life, to listen the stories told by his mother, his friends, his life partners. The tale is interwoven with memories from adventures in the mountains: at the beginning from the rock school of the Lake District and ranges of Scotland, then the Alps, up to the most important expeditions into the Hindukush, the Himalaya, the Peruvian Andes. What may be of an interest to a Polish reader, is that author looks behind the Iron Curtain, to Poland of the 70s and the beginning of the 80s, making an account of visits in the country as a representative of the British Mountaineering Council – the equivalent of Polish PZA – and of expeditions with the leading Polish alpinists: Andrzej Zawada, Voytek Kurtyka, Jan Wolf and the others.

John Porter intertwines his story with numerous anecdotes from life of climbing community. The most interesting stories were brought from the visits in communist Poland. The way the Brits saw Poland of the end of 70s is fascinating, their efforts to understand the incomprehensible commerce of trafficking virtually anything what can be sold, or even making money on expeditions in the high mountains. As it seems, the trafficked goods were also used by the secret services of communist regime. Together with the author, we visit the Tatra in winter, where the Brits meet armed Czechoslovak border force officers during the climb on the ridge. We observe the fascinating poker game between climbers and the party apparatchiks. The most engaging are stories of how Andrzej Zawada smuggled the team of Brits on the train across the USSR in the middle of the Cold War. While the merry British team, unaware of the danger, played cards in their compartment listening to Led Zeppelin, the train’s speakers were transmitting loud songs of the Choir of the Red Army. Zawada borrowed the Macintyre’s ice axe and methodologically smashed all speakers in the carriage, one-by-one, until the Choir was no more. Returning the ice axe to astonished British climbers he said: “We do not allow such a militarism and lack of good taste in Poland”. Zawada’s attitude towards the Soviet Russia is characterised by his commentary on giving the Scotch whisky as a bribe to officers in Moscow: “Polish vodka is far too good for these Russians. To give them Scotch is a crime”. The book is filled with little stories of the kind: stories about climbers from the United Kingdom and about the Poles – like the one about conflict of a gemstone of Voytek Kurtyka and inhabitants of the Afghan village.

“One day as a tiger” has a similar significance for the British himalaism as for the Polish had the “Freedom climbers” by Bernadette McDonald. We get to know the legendary Englishmen, that traced new routes and set new standards in mountains, however, who are often not well known to a Polish reader. In the book stories about everyday life of the climbers mix with the tales of climbing. The book tells how alpinists coped with jobs, relationships, family. All these threads help to understand the lives of protagonists, take away status of super-humans, and show the everyday difficulties they faced on the lowlands, how lost they were, the price they had to pay for the lifestyle they chose. Conversations with Alex’s closest ones bear witness to the tragedy of the situation, seemingly without solution: a passion, that made him who he was, gave him his maturity, at the same time being a very egocentric passion, which leaves no room for the happiness of other people. The passion that requires support from others and a passionate man, that wants to be loved, needs a community and stable life after coming back from expeditions. The book tells the story of how Macintyre perfected his climbing style, and how he kept on losing his nature and relationships with friends in the process. Each step towards even more difficult challenges required from him to be less and less sensitive to problems of the others and to be more and more focused on his goal.

Author invites us to almost philosophical reflections on the purpose of climbing, on its beauty, on what it gives and what it takes. John Porter seems to be asking a question – how to follow the path of passion, not to get lost, not to take one step too far, not to raise the stakes too high, higher than we are willing to pay. Often a reply comes as a sorrow and remorse many years too late. The ideal state of equilibrium described by the author was the moment before entering very dangerous wall of Koh-i-Bandaka, when he felt that there was nothing in the past he wanted to hold on to, nothing in the future he wished to aspire to, except the here and now.

Reading “One day as a tiger” is a great pleasure also because of a vivid language of the author. John Porter describes events and adventures in such a colourful way, that it’s difficult to stop reading. Language used is very illustrative, creative and often reaches out to the slang of climbers of the 70ies and the 80ies. Translating the book into Polish, while keeping the imaginativeness, will be a challenge for translator. One of the pearls prepared by the author is giving the chapters titles related to the names of songs and culture of the time. „Stairway to heaven”, „A walk on the wild side”, „Rocking in the free world” – describing climbing behind the Iron Curtain, “Let it be”, where author meets Alex’s mother, „Wish you were here”….

I can recommend this book by any measure. In my opinion it will soon belong to the canon of mountain literature. This is an incredibly well written account of the times that are long gone, nevertheless have a lot to do with the reality of today. For those who can, I advise reading an original book before the Polish translation becomes available.

Reading “One day as a tiger” I’ve been thinking how much of my comfort I would be ready to sacrifice in order to live Alex’s life, how much would I be willing to risk, how long would I agree to be exhausted and in fear? For Alex Macintyre, it seems, there was no other way. He preferred to “live one day as a tiger than a thousand years as a sheep”.

By Mateusz Gątkowski