Is winter Himalayan mountaineering possible without Artur Hajzer? “Well, they say ‘in for a penny, in for a pound.’ There is a will to finish it, an urge to confirm the Polish leadership in this discipline. It is a wonderful idea and I am making it happen with passion,” he used to say. Although the Gasherbrum expedition, during which he died, took place outside of the Polish Winter Himalayan Mountaineering Project 2010-2015 (Polski Himalaizm Zimowy – PHZ), it had been well known that he went there to build up his stamina for the remaining summits which have not been climbed in winter yet. He was one of the youngest Ice Warriors and has become the eternally young Ice Leader. This article, written by Jagoda Mytych, was originally published in “n.p.m.” magazine in September 2013. Traslated by Jakub Safiak.

Is winter Himalayan mountaineering possible without Artur Hajzer? “Well, they say ‘in for a penny, in for a pound.’ There is a will to finish it, an urge to confirm the Polish leadership in this discipline. It is a wonderful idea and I am making it happen with passion,” he used to say. Although the Gasherbrum expedition, during which he died, took place outside of the Polish Winter Himalayan Mountaineering Project 2010-2015 (Polski Himalaizm Zimowy – PHZ), it had been well known that he went there to build up his stamina for the remaining summits which have not been climbed in winter yet. He was one of the youngest Ice Warriors and has become the eternally young Ice Leader. This article, written by Jagoda Mytych, was originally published in “n.p.m.” magazine in September 2013. Traslated by Jakub Safiak.

“Everyone knows one of his faces, one or a few,” wrote Izabela Hajzer about her husband and best friend. And in fact, you could really separate Artur Hajzer’s resume into a number of people. He was a top quality climber with seven eight-thousanders to his name, a successful businessman, the founding father and chief executive of a project which made the Poles start climbing eight-thousanders in winter again. Even if not all the goals he had set were accomplished successfully, he never gave up. He was well known for his endurance and perseverance as well as his wittiness and willingness to share his knowledge and experience.

Artur died on 07 July 2013 while retreating from Gasherbrum I, one of the two eight-thousanders he had planned to ascend this year to “keep fit and stay in touch with the altitude in case another winter expedition was about to take place in the coming years.” We bid him farewell on 24 July in the arch-cathedral in Katowice, the same church, in which 24 years earlier another service had been performed to commemorate Jerzy Kukuczka. Janusz Majer, not only Artur’s business partner for many years but also a friend, gave a moving speech during the funeral service.

While I was working on this text, he told me: “Everyone knows one of his faces. Just so. I think I knew them all. When you work together, there are many reasons to end friendship, but we made it. We went through a lot of twists and turns.”

Snow Elephant

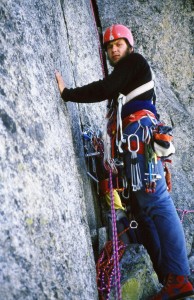

Artur was born on 28 June 1962 in Silesia. He graduated from the University of Katowice with a degree in Cultural Studies but since he was a teenager, he had been active in the Silesian mountaineering circles where he had been nicknamed ‘Elephant’. When he was 14 years of age, he started climbing with the Tatra Scout Club. At the age of 16, he finished the climbing course in the Tatra mountains, so called ‘Betlejemka’. His sporty attitude could already be seen at that time. He climbed Kazalnica Mięguszowska via many routes, Ganek and other faces, and a few difficult routes in the Alps in the Mont Blanc massif, including Petit Dru and Mont Blanc du Tacul.

Artur Hajzer’s later climbing career was closely linked to the Mountaineering Club in Katowice, which at that time was called “the best Himalayan mountaineering club in the world’, as it was the place where Jerzy Kukuczka, Krzystof Wielicki and Ryszard Pawłowski had actively been involved.

“We were one large family in the club. Our lives revolved around the club. We did not only spent time climbing rocks or mountaineering but worked together, partied together and went to concerts together. Artur was a significant individual in the club. He was one of the promising young who did not end up as ‘promising’ but actually achieved a lot by the age of 30,” recalls Janusz Majer, who had been the chairman of the club in Katowice since 1980 and is its honorary member at present.

Hajzer was not only an above-average climber but also a savvy and talented … tailor. He would sew everything for himself and his fellow climbers, from harnesses and backpacks to articles of clothing and down jackets. It was an invaluable experience, taking into account the fact that he was then one of the pioneers of the Polish outdoors industry. He was also familiar with painting – especially at high altitude.

Artur reminisced the summer of 1982 in his book Attack of Despair. “Every day was the same. We did not let the paint rollers out of our hands from dawn till dusk. Fortunately, we spent weekends climbing rocks in the Polish Jurassic Highland, mastering our climbing form. We did not know then which mountains we were about to be tested in.”

And the same year, at the age of 20, with a trip to Rolwaling Himal region, Artur began his Himalayan adventure. The following year, he took part in an expedition to Tirich Mir (7,706m), the highest mountain of the Hindu Kush range. In 1985, he made his first attempt on the south face of Lhotse. The club expedition had already been at Camp V, when it was joined by another member of the Katowice circles – Jerzy Kukuczka.

Regrettably, although Hajzer met his idol and future climbing partner, he lost his current partner, Rafał Chołda, who died climbing Lhotse. Artur wrote that “from the very first moment they tied and shared a rope, they walked the same path.” The expedition was unsuccessful. Almost immediately afterwards, he set out on another one – a winter expedition to climb Kangchenjunga. He reached the summit again and again faced death in the mountains. This time it was Andrzej Czok who lost his life.

Jerzy Kukuczka’s partner

When you look for a phrase to describe Artur Hajzer, one of the first that comes to mind is ‘Jurek Kukuczka’s partner.’ Even though their first expedition was not successful, after Lhotse Hajzer felt much more secure.

“I started believing in myself. I realised that my first steps were analogous to what Jurek had been doing a few years back. Eventually, I felt convinced that the Lhotse failure had not determined it all and the next time – as proven by Jurek’s career – would be better,” Hajzer recalled years later. And it was better, together with Jerzy Kukuczka.

“How about going on an expedition with me? I need a partner. How about that?”

“I am all for it, on spec”, answered Elephant to Kukuś.

“It was very elevating to Artur, he was very pleased. Jurek Kukuczka offered Artur that if he had organised an expedition to Manaslu and a winter expedition to Annapurna, they would climb together. And so it happened, and that is the reason Artur decided not to go with us to climb K2 via the Magic Line route,” recalls Janusz Majer.

“The Manaslu (8,156m) expedition was the most difficult of all our – mine and Jurek’s – successful expeditions. It took place in autumn 1986. We were to attempt the south face of Annapurna (8,091m) in the same season,” wrote Hajzer. On 03 February 1987 they made their first winter ascent together to the summit of an eight-thousander.

Another expedition they went on together was a summer expedition to Shishapangma in August 1987, during which they established a new route on the western ridge. The same year, Artur made another attempt on the south face of Lhotse during an international expedition organised by Krzysztof Wielicki. The expedition was a failure. In 1988, he accompanied Jurek Kukuczka, this time ascending the west Annapurna via a new route. A year later he returned for the third time to the south face of Lhotse. That time, the international expedition was organised by the Kukuczka’s ‘greatest rival’ – Rainhold Messner.

“After that expedition I came to a conclusion that another attempt would be a waste of time,” Artur writes in Attack of Despair. That is why he did not join Kukuczka during his attempt.

“It was clear that Artur had equalled his master and his own ambition took the floor. He wanted to bring his own mountaineering projects to life,” recalls Janusz Majer.

On 24 October 1989, Jerzy Kukuczka fell of the south face of Lhotse and died. Artur Hajzer gave up climbing for a long time.

“It took me 15 years to get over it,” that is all he told me about that incident and switched off for a while. He looked as if he was not talking about something in the past but processing news that had just arrived. When he returned to Lhotse under the Polish Winter Himalayan Mountaineering Project, he said that it was ‘a conversation with ghosts.’

Rescuing and rescued

1989 was as equally tragic to Polish Himalayan mountaineering as 2013. In 1989, five eminent climbers died in an avalanche on Lho La pass while climbing Mount Everest: Eugeniusz Chrobak (expedition leader), Zygmunt Andrzej Heinrich, Mirosław ‘Falco’ Dąsal, Wacław Otręba and Mirosław Gardzielewski. The only survivor was Andrzej Marciniak, suffering from snow blindness while awaiting rescue. Hajzer was in Kathmandu at that time. With no hesitation he set about organising a complicated rescue mission from China, as it was the only possible way.

“At that time, people were protesting in Tiananmen Square. Borders were tightly shut. The American Embassy needed to exert pressure. To organise the rescue mission was probably more difficult than to pull it off. But I got instructed by Janusz Majer that either I would do something or it was done and dusted. In such moments, there is really no room to debate, or it is all over,” recalled Artur Hajzer.

“It seemed to me that Artur was the only person able to organise a rescue missions under those complicated circumstances. Even though there were excellent climbers in the base camp, it was impossible to approach from our side because of the avalanche danger. The only option left was unconventional. It was a challenge to Artur, the quintessence of his way of life. He started acting immediately. He was talking to Messner. Messner was talking to the Italian ambassador who was playing tennis with the Russian ambassador the following day. It was all about getting to the Chinese and get their permission for the mission,” said Janusz Majer.

For a daring rescue mission on Mount Everest Artur received the Polish Olympics Committee Fair Play Award. 20 years later, Andrzej Marciniak died while climbing in the Tatras. When Hazjer was asked about it, he emphasised that the most important aspect of it was that he had managed to give him those extra 20 years.

Not only did Hajzer recue people but was also rescued by them. In 2005, on Broad Peak, he broke his leg at almost 8,000m. Piotr Pustelnik, who was climbing with him then, led the rescue mission. In February 2008, he was taken by an avalanche on the south ridge of Ciemniak in the west Tatras. He managed to stay close to the surface and thanks to a well-organized TOPR mission, he was rescued unscathed and even got a reputation of ‘always landing on his feet.’ For walking outside of the designated tourist route, the Tatra National Park board of directors gave him a symbolic disciplinary warning.

“February 2008, the Tatras. Objective: to traverse the entire Tatra ridge non-stop. I am walking with three experienced Himalayan mountaineers. I feel safe. We are in our twenty second hour of walking, we are ascending Ciemniak. Artur is first and suddenly disappears. Panic stations – Piotrek is trying to get reception and notify TOPR. Darek is going downhill. Done, TOPR is notified, they are coming. Hearing the helicopter, we walk slowly down in silence. Minutes are passing. And then I got a text message from Artur: I am alive. My first thought: Artur, you are invincible. That thought is with me today as well,” recalls Tamara Styś, a Himalayan mountaineer.

Businessman

After 1989, he withdrew from active climbing and together with Janusz Majer took to business, which gave birth to a brand that became cult in the 90s – Alpinus.

“After Everest, Artur came up with this idea of 14 eight-thousanders in a year. We were supposed to have one million dollars to do it. We were sorting out permissions. The entire organisation process was well advanced. We even had business cards. In autumn 1989, when Jurek was on Lhotse, Artur and I went to lSPO to look for a sponsor for our project. We talked to a number of people, including Albrecht von Dewitz, the founder of Vaude, a huge German outdoor brand. Eventually, we did not get a sponsor for our Himalayan project but a business partner,” says Janusz Majer. “First, we sewed for Vaude and then directly for Alpinus. From Vaude we got the know-how. Our advantage was that we knew the product inside out. Our products were known to be of good quality. Even today I meet people wearing our jackets made in the 90s,” he adds.

High quality materials, advanced technologies and, at the same time, limited interest of the Polish people in the outdoor market resulted in financial difficulties of the company, leading to its bankruptcy. The founders were not put off, though. Hajzer and Majer’s new project was another brand which was more affordable to the customer. HiMountain products are visible almost everywhere in the Polish mountains.

“We had already had experience gained during the liquidation of our first enterprise, so when we were creating HiMountain, we were trying to eliminate the root causes of our previous failure. But we had never given up on quality. Artur was very creative at work and kept following all current market trends. He knew how to build a team and come up with new projects which would attract people to participate in their implementation,” says Janusz Majer.

After 15 years in business, Artur realised that ‘he could not live peacefully without mountains.‘ He returned to climbing in 2005. First, almost instantly, he went to climb Broad Peak with Piotr Pustelnik and then Dhaulagiri with Robert Szymczak.

Winter expeditions leader

Artur’s business approach can be traced in the way the Polish Winter Himalayan Mountaineering Project 2010-2015 functions, which, according to Artur Hajzer, has been born out of a need to convince PZA to fund expeditions in the highest mountains.

“The fact that the project exists depends 90% on office and managerial work and one day I should really write what it looks like from behind the desk,” Artur used to joke.

And it looked like this. On 14 November 2009, 3 potential Himalayan mountaineers showed up in his office: Arek Grządziel, Jacek Czech and Irek Waluga. The next day was the deadline for funding applications.

“We knew PZA would not give a penny for a regular route climb, even in winter, if the success were not guaranteed. Robert Szymczak and I had just been refused financial support for a winter Broad Peak expedition 2008/2009. It was then when I came up with this idea that I would draft a project which would not be about climbing via regular routes but winter expeditions in the years to come,” recalled Hajzer.

The seed took root and in May 2010, already under the Polish Winter Himalayan Mountaineering Project 2010-2015, an expedition was organised to climb Nanga Parbat. Artur reached the summit with Robert Szymczak and during the second attack, Marcin Kaczan, one of the younger members of the team, ascended to the summit. ‘The young’ proved themselves again during the Elbrus Race. Andrzej Bargiel and Ola Dzik finished the race in record time.

The winter expedition to Broad Peak was not successful. Not everything went as intended during the autumn Makalu expedition, either. Even though on 30 September 2011 Artur managed to ascend to the summit, during the five days long dramatic return, Maciej Stańczak and Tomasz Wolfrat suffered severe frostbites. Since then, Hajzer had been more and more often labelled as ‘the one exposing the young to danger.’ Although comments referring to ‘Hajzer’s pre-school’ were hurtful, he believed that when the long awaited success would be achieved, it would also result in winning the favour of the media and the society. The winter ascent on Gasherbrum 1 in March 2012 by Adam Bielecki and Janusz Gołąb had been such a success.

Hajzer-chief was bursting with pride. He could plan the next integration expeditions, test new climbers and even contemplate a winter expedition on K2. There was a sponsor and even the presidential patronage.

“In the end, there were other expeditions: spring to Manaslu, summer to K2 and autumn to Lhotse. Three integration expeditions in one year! There had never been a time in the history of Polish Himalayan mountaineering during which the highest mountains would be so accessible,” Hazjer remembered that period with joy. During the expedition to Lhotse he singled out another climber who, together with Adam Bielecki, was to measure himself against winter summits. It was Adam Małek.

“Before I joined PHZ, I and my climbing partner, Mateusz Grobel, had a closer look at it. I admit I was a bit sceptical about Artur Hajzer and the people he had been sending on integration expeditions. I had always thought that they were always triathlon specialists or adventure racing runners, rarely real climbers. It surprised me and put me off. However, I did not want to be judgemental without learning about Himalayan mountaineering first,” recalls Małek. “When I started to have more personal contact with Artur I saw a completely different picture than the one I had imagined. It was a year of very close contact. When you are stuck with somebody for two months on an expedition all masks are shed. He badly needed climbers for the project but very few enrolled. The amazing thing was that in Artur Hazjer’s times, if a person wanted to climb an eight-thousander, all you needed to do was to have a proper list of accomplishments and a wish to go. Never before had the young had such an easy access to the highest mountains. If you were a climber, wanted to test yourself and go in winter time, you could. Probably for 20 years no-one had ever made the highest mountains so within the young arm’s reach. He offered a chance and an opportunity to make the best of it,” points out the young Himalayan mountaineer.

As Małek admits that he misjudged Hajzer in the beginning, the other had a hunch that the young would prove himself and took him on board for the winter Broad Peak expedition, together with Adam Bielecki, who had already become a star; Maciej Berbeka, a distinguished elder; and Tomek Kowalski, who was making his debut at eight thousand. Krzysztof Wielicki was the head of the expedition. Hazjer followed the course of the expedition – its success and subsequent tragedy – from Poland. Berbeka and Kowalski stayed on Broad Peak forever. The same thing happened as after Makalu – an avalanche of criticism fell over Artur Hajzer.

Hajzer was still explaining Broad Peak when another integration expedition set out on Dhaulagiri in April. The Gasherbrum expeditions appeared to be an attempt to run away from the entire world. Partly, it helped him to distance himself from the media and Internet discussions but it was also another step towards K2 in winter – a step which has never been taken…

“I think the most important lesson to be learnt from Artur Hazjer is the Gasherbrum one, when he died. It was his last lecture on high mountains. People die in the mountains, even the best ones,” says Małek.

Mentor

He was never condescending towards others, never at a distance and never claimed that ‘it had been better in his times.’ All the younger generation climbers who had the privilege to learn under Elephant’s guidance emphasise that unanimously. Where did his openness come from? Perhaps it had its origins in the fact that he still remembered how he had been a rookie trying to make it into the first league.

“Our contact with the great ones was official and courteous […]. Rookies had no say, they were just there in the back line, on the floor,” he wrote in his memoirs.

“I think it was hard for him to be the two – mate and mentor – at the same time. His jokes and sense of humour generated a friendly atmosphere, but he would never forget he was the chief. Artur commanded respect with the list of climbs he had made and he was a genuine chief. It happened at times that he was even firm and resolute. With him, the democratic style was alternated with the authoritarian, depending on need. He knew how to make a decision and command respect. People really respected him. With his experience, he was predisposed to managing by delegation. And if you wanted to manage Himalayan mountaineers with less experience or run a project like the Polish Winter Himalayan Mountaineering Project 2010-2015, you needed to be a leader,” recalls Ola Dzik, who, in spite of her young age, knows the dilemmas of leading an expedition. She was the head of the Nanga Parbat expedition when their camp was attacked by terrorists.

“Artur was that type of a leader who would never tell us what we should do but ask us what we would do. If he saw that we had done something in a wrong way, he would suggest another solution. He kept observing our every move, every decision. But most of all he kept pushing us to think independently, as a result of which we were learning much faster. He was a natural school principal at a natural Himalayan mountaineering school. He had us under his care but never imposed his will. Understanding was reached through discussions, and there were plenty in the mess. And he was a man who never got bored. He taught himself Nepalese, Sherpa, to be exact. He practised, spoke and wrote and by the end of the expedition even read in it. He listened to what people had to say. He allowed criticism: after each expedition he improved and modified the project,” adds Artur Małek.

Even though Hajzer is depicted mostly as a teacher of the younger generation of Himalayan mountaineers and a generation mediator, he himself loved learning new things.

“He got along extremely well with any new group of climbers. He could talk to the young; exchanged emails; actively used Facebook; he was open-minded to new ideas and knowledge. Because he had taken a break from climbing, he soaked knowledge up later. His experience from expeditions constantly helped us to improve our gear. There had never been a person who would bridge the generations the way he did,” claims Janusz Majer.

Dreamer

He never concealed the fact that the reactivation of winter Himalayan mountaineering in Poland was not only a patriotic and sports idea he borrowed from Andrzej Zawada and Krzystof Wielicki but also his great ambition. He really wanted to do K2 in winter. It was meant to have been the last expedition he wanted to lead. The bar was so high – stirring criticism – but no one was really surprised.

“The problem is that I always come up with something big. And once it becomes great people show up who would gladly take it away from me. And since I am not going to run out of ideas, there will always be critical voices,” he explained before the Gasherbrum expedition which was supposed to have been ‘a walk in the park’ and definitely not the last climb in his career. He did his best to avoid any possible controversy: both he and Marcin Kaczan financed the expedition with their own money, never used public funding. However, he could not foresee that this expedition would receive the greatest publicity in his career.

“We had different opinions on various subjects and we argued, but those were always fights at a certain level. He had class, which is typical of the top-shelf climbers. It is sad to read publications which are motivated solely by morbid fascination with death. Sometimes the same people, who have lately criticised Artur and PHZ, now write how magnificent he was. But that is a consequence of the Himalayan mountaineering entering pop culture of the lowest standard. When criticism is in demand, people criticise. When praise is in demand, the same people are ready to praise. I do not like it. Artur was glad that the media had taken interest in the Himalayan mountaineering. Now it has slightly turned against him. You need a simple message in pop culture; there is no room for complexity or an analysis of facts. We will have plenty of time to contemplate what kind of a person he was and how valuable his work was once the media hiccups and haters and Internet trolls’ accompaniment have ceased,” says Old Dzik, sociologist and psychologist by education.

And maybe we will live to see – not only in Poland but worldwide – a publication worthy of his person and his project.

“This is supposed to be a five-year project. It has been three years so far and as a result the Polish climbers were the first to ascend to the summit of Gasherbrum 1 in winter in great style. The expedition was organised in such a way as Artur had dreamt. The experience of previous expeditions was used, both positive as well as negative. It is a fact duly noted in the history of Himalayan mountaineering and according to the ExplorersWeb portal that feat ranked higher than the jump made by Felix Baumgartner. Then, there was the winter conquest of Broad Peak. It is an achievement of the same calibre, burdened with tragedy. And then, unfortunately, it all reverted back to the heroic epoch of reminiscing about the 80s, the standards were gone,” recalls Janusz Majer and makes it clear that it is worth holding off commenting on the last winter expedition until the PHZ committee has issued an official report.

Everybody knew one of Artur Hajzer’s faces. Today, everyone tries to learn from the lessons they got from him. “Because this is history, because these are dreams, because this is history worth remembering,” a verse from the lyrics of Dreams by DKA which had almost immediately become an anthem for ‘Race for Elephant’ which was organised in Katowice to commemorate Artur Hazjer. It also proves that – even for people who privately do not have much to do with the highest mountains – it matters a lot that the Polish people have taken to exploring mountains in winter again. Because of Elephant, no one is likely to say ‘the grass is greener on the other side.’ It is green right here and we are proud of it.

“The world needs daredevils. They inspire, challenge, encourage. They stir sparks and ignite flames burning long after they are dead. They have the courage to do what they deem impossible. But not without a cost,” wrote Maria Coffey in Where the Mountain Casts Its Shadow: The Dark Side of Extreme Adventure. The world needs people like Artur Hajzer.

Bernadette McDonald

Writer, journalist, author of Freedom Climbers

I met Artur during the years that I was working on the book. At first I felt that he was quite wary of me, and a bit reserved. But gradually his quirky sense of humour emerged. Not only that, but his great sense of Polish history. Over the months that followed, Artur sent me countless emails, sometimes with not one word of text, just a link to some bit of history that he felt I should read or some Polish composer I should listen to or some piece of art that I should view in order to better understand the Polish soul. It occurred to me during that time that it was history that really inspired him, at least as much as the mountains. But I think it was that historical context that helped him understand his important role in reviving the Polish winter programme in the highest mountains. It was this goal that combined his two great passions. But always with a sense of humour! That’s how I will remember Artur Hajzer.

Janusz Majer

Himalayan mountaineer, Hajzer’s friend

“Everything Artur did in life, his goals, was all on the verge of dreams. But he could make them come true. The Polish Winter Himalayan Mountaineering Project is the quintessence of his actions. Once he committed to something, he was all the way in. I admire him for his come-back to active climbing in the Himalayas and for the way he had chosen to get ready. He trained consistently. He had a coach and sports medicine physicians who fixed him up. You must remember he was over 40, slightly overweight and a smoker. He trained almost every day until he became extremely physically strong and capable. During the first winter expedition to Broad Peak, he reached the camp right after the high altitude carriers. They patted him on the shoulder saying “old is good,” to which he would reply “I am not that old yet!“

Aleksandra Dzik

Himalayan mountaineer, Snow Leopard award winner

Artur was no show-off. He was modest, as regards the list of the climbs he had made. He would start talking about himself and his achievements only when asked. And he did not have the habit of saying: “In my prime we were…” He had a list of climbs that would knock you out but felt no urge to talk about it to build up his prestige. He had this overwhelming advantage over us and I think he was well aware of it. Whenever asked, though, he would share his enormous knowledge and tell numerous stories and anecdotes. He knew a lot about history and political and social problems of any given mountain region. He knew the history of the conquest of the mountains. He never approached expeditions mechanically, just to “arrive, get up there and back.” Behind the mountain he saw the country, the region, its people. He had a broad knowledge of it all. When we were in Islamabad, he tested and questioned me on geography, politics, for example, asked about the countries surrounding Pakistan, what that conflict was all about…

Artur Małek

Himalayan mountaineer, Conqueror of Broad Peak in winter

A great thing about Artur was that he could combine the new, namely the young, with the old, the experience of the 80s. It was phenomenal. He used all technological advancements that would make it easier to climb and which had not been available in the 80s. He was neither prejudiced nor did he have any qualms. He would introduce only the best novelties. He was doing his best to improve Polish Himalayan mountaineering. When Andrzej Bargiel introduced him to stretching and stretched him, he would do stretching himself, every day after trekking or climbing, he would wear his long johns and do stretching in the mess with everybody around. I was wrecked and would not move a finger. But he would. Some elders objected to using new technologies, Artur had no objections. He was the one to introduce ‘camelback’ to winter Himalayan mountaineering. The same with gels. He used to say that he was not going anywhere without them. That was the quintessence of Artur Hejzer: he was the mediator between the past and the present. I do not know if there is another person like that in Poland or even worldwide.

Agnieszka Bielecka

Himalayan mountaineer, Participant in expeditions organised under PHZ

I met Artur for the first time at a job interview. I had applied for the position of base camp manager during the winter expedition to Gasherbrum 1 and Artur thoroughly questioned me how I could contribute to the expedition: my knowledge of PR, writing skills, photography, video edition, etc. From the very start our relationship was very professional. I was the base camp manager but when one of our Pakistani partners got frostbitten, I had an opportunity to leave for Camp 1. Afterwards, Artur offered me a place on another expedition, which was initially planned on Cho Oyu but eventually ended up on Lhotse. If it had not been for him, I would not have been to the Himalayas at all.

There is no reason why winter Himalayan mountaineering should be a man’s world. Artur was honest as regards assessing climbers. He judged and treated people by their merits, not by gender. Perhaps, in the beginning, he was not entirely convinced that female participation in expeditions was a good idea but already on Lhotse he said that he had not understood prejudices against women. He could look at things beyond the gender prism. We had our fights at times, he could be equally unbearable. But as far as mountains were concerned, he had always been right. It is said that nobody is irreplaceable but for me, taking into account his ability to combine marketing, organisation and leadership skills with the knowledge of the mountains, for me, Artur was one of a kind.

Reinhold Messner

First climber to ascend all fourteen eight-thousanders in the Himalayan and Karakoram mountain ranges

I met Artur by the end of the 80s. He was a member of a small expedition I had organised. I remember him as sensible, witty and very competent. He was a tough type. He had already climbed half a dozen eight-thousanders, some in winter. He died at the age of 51, the best age for a Himalayan mountaineer. […] I am shocked and I am sad.